Asl Sign For What Happened

| American Sign Language | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Native to | United states of america, Canada |

| Region | English language-speaking N America |

| Native speakers | 250,000–500,000 in the U.s.a. (1972)[1] : 26 L2 users: Used as L2 by many hearing people and by Hawaii Sign Language signers. |

| Linguistic communication family unit | French Sign-based (possibly a creole with Martha'due south Vineyard Sign Language)

|

| Dialects |

|

| Writing organization | None are widely accepted si5s (ASLwrite), ASL-phabet, Stokoe notation, SignWriting |

| Official status | |

| Official language in | none |

| Recognised minority | Ontario only in domains of: legislation, educational activity and judiciary proceedings.[2] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-iii | ase |

| Glottolog | asli1244 ASL familyamer1248 ASL proper |

Areas where ASL or a dialect/derivative thereof is the national sign language Areas where ASL is in significant employ alongside another sign linguistic communication | |

American Sign Language (ASL) is a tongue[four] that serves as the predominant sign language of Deaf communities in the United states of america of America and most of Anglophone Canada. ASL is a complete and organized visual linguistic communication that is expressed by employing both transmission and nonmanual features.[5] Besides North America, dialects of ASL and ASL-based creoles are used in many countries around the world, including much of West Africa and parts of Southeast Asia. ASL is too widely learned equally a 2d language, serving as a lingua franca. ASL is most closely related to French Sign Linguistic communication (LSF). It has been proposed that ASL is a creole linguistic communication of LSF, although ASL shows features atypical of creole languages, such as adhesive morphology.

ASL originated in the early 19th century in the American School for the Deaf (ASD) in W Hartford, Connecticut, from a situation of language contact. Since so, ASL use has been propagated widely past schools for the deafened and Deaf customs organizations. Despite its wide use, no authentic count of ASL users has been taken. Reliable estimates for American ASL users range from 250,000 to 500,000 persons, including a number of children of deaf adults and other hearing individuals.

ASL signs have a number of phonemic components, such equally motility of the face, the body, and the hands. ASL is not a form of pantomime although iconicity plays a larger part in ASL than in spoken languages. English language loan words are often borrowed through fingerspelling, although ASL grammar is unrelated to that of English. ASL has verbal agreement and aspectual marker and has a productive organization of forming agglutinative classifiers. Many linguists believe ASL to be a subject field–verb–object (SVO) language. Nevertheless, there are several alternative proposals to account for ASL word order.

Nomenclature [edit]

Travis Dougherty explains and demonstrates the ASL alphabet. Vocalism-over interpretation by Gilbert G. Lensbower.

ASL emerged every bit a language in the American School for the Deaf (ASD), founded by Thomas Gallaudet in 1817,[vi] : 7 which brought together Old French Sign Linguistic communication, various village sign languages, and home sign systems. ASL was created in that situation by language contact.[7] : xi [a] ASL was influenced by its forerunners only distinct from all of them.[vi] : 7

The influence of French Sign Linguistic communication (LSF) on ASL is readily credible; for instance, it has been found that about 58% of signs in modern ASL are cognate to Sometime French Sign Language signs.[6] : 7 [vii] : fourteen However, that is far less than the standard lxxx% mensurate used to make up one's mind whether related languages are really dialects.[7] : 14 That suggests that nascent ASL was highly affected by the other signing systems brought by the ASD students although the school'southward original director, Laurent Clerc, taught in LSF.[6] : seven [7] : fourteen In fact, Clerc reported that he oft learned the students' signs rather than carrying LSF:[7] : fourteen

I run across, even so, and I say information technology with regret, that any efforts that we take made or may still exist making, to do better than, we have inadvertently fallen somewhat back of Abbé de l'Épée. Some of usa have learned and still learn signs from uneducated pupils, instead of learning them from well instructed and experienced teachers.

—Clerc, 1852, from Woodward 1978:336

It has been proposed that ASL is a creole in which LSF is the superstrate language and the native hamlet sign languages are substrate languages.[viii] : 493 However, more recent research has shown that modernistic ASL does not share many of the structural features that characterize creole languages.[8] : 501 ASL may accept begun as a creole and then undergone structural change over time, merely it is also possible that it was never a creole-type language.[8] : 501 There are modality-specific reasons that sign languages tend towards agglutination, such as the ability to simultaneously convey data via the face, head, body, and other body parts. That might override creole characteristics such as the tendency towards isolating morphology.[8] : 502 Additionally, Clerc and Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet may have used an artificially constructed course of manually coded language in instruction rather than true LSF.[8] : 497

Although the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia share English language as a common oral and written language, ASL is not mutually intelligible with either British Sign Language (BSL) or Auslan.[9] : 68 All iii languages show degrees of borrowing from English, only that alone is non sufficient for cross-language comprehension.[9] : 68 It has been found that a relatively high percentage (37–44%) of ASL signs have similar translations in Auslan, which for oral languages would suggest that they belong to the aforementioned language family.[9] : 69 Withal, that does not seem justified historically for ASL and Auslan, and it is likely that the resemblance is acquired by the higher degree of iconicity in sign languages in general as well as contact with English.[nine] : seventy

American Sign Language is growing in popularity in many states. Many loftier school and university students desire to accept it every bit a foreign language, but until recently, information technology was usually not considered a creditable foreign language elective. ASL users, however, have a very distinct civilisation, and they interact very differently when they talk. Their facial expressions and hand movements reflect what they are communicating. They also have their ain sentence structure, which sets the linguistic communication apart.[ten]

American Sign Language is now being accustomed past many colleges equally a language eligible for strange language course credit;[11] many states are making information technology mandatory to accept it every bit such.[12] in some states nevertheless, this is only true with regard to high school coursework.

History [edit]

A sign linguistic communication interpreter at a presentation

Prior to the nascency of ASL, sign language had been used past diverse communities in the United States.[vi] : v In the United States, as elsewhere in the earth, hearing families with deafened children accept historically employed advertisement hoc home sign, which often reaches much higher levels of sophistication than gestures used by hearing people in spoken chat.[half dozen] : 5 As early as 1541 at first contact by Francisco Vásquez de Coronado, there were reports that the Indigenous peoples of the Bang-up Plains widely spoke a sign language to communicate across vast national and linguistic lines.[xiii] : 80

In the 19th century, a "triangle" of hamlet sign languages developed in New England: one in Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts; 1 in Henniker, New Hampshire, and one in Sandy River Valley, Maine.[14] Martha'due south Vineyard Sign Linguistic communication (MVSL), which was specially important for the history of ASL, was used mainly in Chilmark, Massachusetts.[six] : 5–6 Due to intermarriage in the original community of English settlers of the 1690s, and the recessive nature of genetic deafness, Chilmark had a loftier 4% rate of genetic deafness.[half-dozen] : 5–6 MVSL was used fifty-fifty by hearing residents whenever a deaf person was nowadays,[6] : five–6 and also in some situations where spoken language would be ineffective or inappropriate, such every bit during church sermons or betwixt boats at sea.[15]

ASL is thought to take originated in the American School for the Deaf (ASD), founded in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1817.[six] : 4 Originally known as The American Asylum, At Hartford, For The Teaching And Education Of The Deaf And Dumb, the school was founded by the Yale graduate and divinity pupil Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet.[sixteen] [17] Gallaudet, inspired by his success in demonstrating the learning abilities of a immature deaf daughter Alice Cogswell, traveled to Europe in order to larn deaf educational activity from European institutions.[16] Ultimately, Gallaudet chose to adopt the methods of the French Institut National de Jeunes Sourds de Paris, and convinced Laurent Clerc, an assistant to the school'south founder Charles-Michel de l'Épée, to back-trail him back to the United States.[16] [b] Upon his return, Gallaudet founded the ASD on April 15, 1817.[16]

The largest group of students during the first seven decades of the school were from Martha'due south Vineyard, and they brought MVSL with them.[7] : 10 There were also 44 students from around Henniker, New Hampshire, and 27 from the Sandy River valley in Maine, each of which had their own village sign language.[7] : eleven [c] Other students brought knowledge of their own home signs.[7] : 11 Laurent Clerc, the get-go teacher at ASD, taught using French Sign Language (LSF), which itself had developed in the Parisian school for the deaf established in 1755.[6] : vii From that state of affairs of language contact, a new linguistic communication emerged, at present known equally ASL.[6] : 7

American Sign Language Convention of March 2008 in Austin, Texas

More schools for the deaf were founded afterward ASD, and noesis of ASL spread to those schools.[vi] : 7 In addition, the rise of Deaf community organizations bolstered the continued use of ASL.[6] : 8 Societies such every bit the National Association of the Deaf and the National Fraternal Lodge of the Deaf held national conventions that attracted signers from across the country.[7] : 13 All of that contributed to ASL'due south wide utilise over a big geographical area, singular of a sign language.[7] : 14 [7] : 12

Up to the 1950s, the predominant method in deafened education was oralism, acquiring oral language comprehension and product.[twenty] Linguists did not consider sign linguistic communication to exist true "language" but as something inferior.[20] Recognition of the legitimacy of ASL was achieved past William Stokoe, a linguist who arrived at Gallaudet University in 1955 when that was still the dominant assumption.[xx] Aided past the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, Stokoe argued for manualism, the use of sign language in deaf education.[20] [21] Stokoe noted that sign linguistic communication shares the of import features that oral languages have as a means of communication, and even devised a transcription system for ASL.[20] In doing and so, Stokoe revolutionized both deafened instruction and linguistics.[20] In the 1960s, ASL was sometimes referred to as "Ameslan", but that term is at present considered obsolete.[22]

Population [edit]

Counting the number of ASL signers is difficult because ASL users have never been counted past the American census.[1] : 1 [d] The ultimate source for electric current estimates of the number of ASL users in the U.s. is a report for the National Census of the Deaf Population (NCDP) past Schein and Delk (1974).[1] : 17 Based on a 1972 survey of the NCDP, Schein and Delk provided estimates consistent with a signing population between 250,000 and 500,000.[1] : 26 The survey did not distinguish between ASL and other forms of signing; in fact, the name "ASL" was not all the same in widespread employ.[1] : 18

Incorrect figures are sometimes cited for the population of ASL users in the United States based on misunderstandings of known statistics.[1] : xx Demographics of the deaf population have been dislocated with those of ASL utilize since adults who become deaf late in life rarely utilize ASL in the domicile.[1] : 21 That accounts for currently-cited estimations that are greater than 500,000; such mistaken estimations can achieve as high equally fifteen,000,000.[one] : i, 21 A 100,000-person lower jump has been cited for ASL users; the source of that figure is unclear, but information technology may exist an guess of prelingual deafness, which is correlated with but non equivalent to signing.[ane] : 22

ASL is sometimes incorrectly cited as the third- or fourth-most-spoken language in the The states.[1] : 15, 22 Those figures misquote Schein and Delk (1974), who really concluded that ASL speakers constituted the third-largest population "requiring an interpreter in court".[i] : xv, 22 Although that would make ASL the third-well-nigh used linguistic communication amongst monolinguals other than English, it does not imply that it is the quaternary-most-spoken language in the United States since speakers of other languages may also speak English.[1] : 21–22

Geographic distribution [edit]

ASL is used throughout Anglo-America.[7] : 12 That contrasts with Europe, where a variety of sign languages are used within the same continent.[7] : 12 The unique situation of ASL seems to accept been caused past the proliferation of ASL through schools influenced by the American School for the Deaf, wherein ASL originated, and the rise of community organizations for the Deaf.[7] : 12–xiv

Throughout West Africa, ASL-based sign languages are signed by educated Deaf adults.[23] : 410 Such languages, imported by boarding schools, are often considered by associations to be the official sign languages of their countries and are named accordingly, such every bit Nigerian Sign Language, Ghanaian Sign Language.[23] : 410 Such signing systems are institute in Benin, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Liberia, Islamic republic of mauritania, Republic of mali, Nigeria, and Togo.[23] : 406 Due to lack of data, it is still an open question how similar those sign languages are to the diversity of ASL used in America.[23] : 411

In addition to the same Westward African countries, ASL is reported to be used every bit a first language in Barbados, Bolivia, Cambodia[24] (aslope Cambodian Sign Language), the Fundamental African Republic, Chad, Mainland china (Hong Kong), the Democratic Congo-brazzaville, Gabon, Jamaica, Republic of kenya, Madagascar, the Philippines, Singapore, and Zimbabwe.[25] ASL is also used as a lingua franca throughout the deafened world, widely learned as a second language.[25]

Regional variation [edit]

Sign production [edit]

Sign product tin often vary according to location. Signers from the South tend to sign with more than flow and ease. Native signers from New York accept been reported as signing comparatively quicker and sharper. Sign product of native Californian signers has also been reported equally beingness fast every bit well. Research on that phenomenon often concludes that the fast-paced production for signers from the coasts could be due to the fast-paced nature of living in large metropolitan areas. That conclusion besides supports how the ease with which Southern sign could be caused by the low-key environment of the South in comparison to that of the coasts.[26]

Sign product can also vary depending on age and native linguistic communication. For example, sign production of letters may vary in older signers. Slight differences in finger spelling production tin be a point of age. Additionally, signers who learned American Sign Language as a second language vary in production. For Deaf signers who learned a different sign language earlier learning American Sign Language, qualities of their native language may show in their ASL product. Some examples of that varied production include fingerspelling towards the body, instead of abroad from it, and signing certain motility from bottom to superlative, instead of top to bottom. Hearing people who learn American Sign Linguistic communication besides have noticeable differences in signing production. The near notable production deviation of hearing people learning American Sign Language is their rhythm and arm posture.[27]

Sign variants [edit]

Virtually popularly, at that place are variants of the signs for English language words such equally "altogether", "pizza", "Halloween", "early on", and "shortly", merely a sample of the well-nigh unremarkably recognized signs with variant based on regional change. The sign for "schoolhouse" is unremarkably varied between blackness and white signers. The variation between signs produced past black and white signers is sometimes referred to as Black American Sign Linguistic communication.[28]

History and implications [edit]

The prevalence of residential Deaf schools tin can account for much of the regional variance of signs and sign productions beyond the Us. Deaf schools ofttimes serve students of the state in which the schoolhouse resides. That express access to signers from other regions, combined with the residential quality of Deaf Schools promoted specific use of certain sign variants. Native signers did non accept much access to signers from other regions during the beginning years of their teaching. It is hypothesized that considering of that seclusion, certain variants of a sign prevailed over others due to the selection of variant used by the educatee of the schoolhouse/signers in the community.

Even so, American Sign Language does not announced to be vastly varied in comparison to other signed languages. That is because when Deaf education was beginning in the United States, many educators flocked to the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut, whose central location for the outset generation of educators in Deafened instruction to learn American Sign Language allows ASL to be more standardized than its variant.[28]

Varieties [edit]

Most – General sign (Canadian ASL)[29]

About – Atlantic Variation (Canadian ASL)[29]

About – Ontario Variation (Canadian ASL)[29]

Varieties of ASL are found throughout the globe. There is petty difficulty in comprehension among the varieties of the United States and Canada.[25]

Just as there are accents in speech, in that location are regional accents in sign. People from the South sign slower than people in the North—even people from northern and southern Indiana accept unlike styles.

Mutual intelligibility among those ASL varieties is loftier, and the variation is primarily lexical.[25] For example, there are 3 different words for English virtually in Canadian ASL; the standard fashion, and two regional variations (Atlantic and Ontario).[29] Variation may also be phonological, meaning that the aforementioned sign may exist signed in a different way depending on the region. For instance, an extremely common type of variation is betwixt the handshapes /i/, /50/, and /5/ in signs with one handshape.[30]

There is likewise a singled-out variety of ASL used by the Black Deaf community.[25] Black ASL evolved as a result of racially segregated schools in some states, which included the residential schools for the deaf.[31] : iv Blackness ASL differs from standard ASL in vocabulary, phonology, and some grammatical structure.[25] [31] : 4 While African American English (AAE) is by and large viewed as more than innovating than standard English, Black ASL is more conservative than standard ASL, preserving older forms of many signs.[31] : 4 Black sign language speakers use more two-handed signs than in mainstream ASL, are less likely to show assimilatory lowering of signs produced on the forehead (e.g. KNOW) and use a wider signing infinite.[31] : 4 Mod Black ASL borrows a number of idioms from AAE; for instance, the AAE idiom "I feel you" is calqued into Black ASL.[31] : 10

ASL is used internationally as a lingua franca, and a number of closely related sign languages derived from ASL are used in many dissimilar countries.[25] Even so, there have been varying degrees of divergence from standard ASL in those imported ASL varieties. Bolivian Sign Language is reported to exist a dialect of ASL, no more divergent than other acknowledged dialects.[32] On the other hand, information technology is besides known that some imported ASL varieties have diverged to the extent of being separate languages. For example, Malaysian Sign Language, which has ASL origins, is no longer mutually comprehensible with ASL and must be considered its own language.[33] For some imported ASL varieties, such as those used in West Africa, it is yet an open up question how like they are to American ASL.[23] : 411

When communicating with hearing English language speakers, ASL-speakers oftentimes employ what is unremarkably called Pidgin Signed English (PSE) or 'contact signing', a blend of English language structure with ASL vocabulary.[25] [34] Various types of PSE exist, ranging from highly English-influenced PSE (practically relexified English) to PSE which is quite close to ASL lexically and grammatically, but may alter some subtle features of ASL grammer.[34] Fingerspelling may be used more oft in PSE than information technology is normally used in ASL.[35] There have been some constructed sign languages, known as Manually Coded English (MCE), which friction match English grammar exactly and simply supervene upon spoken words with signs; those systems are not considered to be varieties of ASL.[25] [34]

Tactile ASL (TASL) is a variety of ASL used throughout the U.s. by and with the deaf-blind.[25] It is peculiarly common amongst those with Usher's syndrome.[25] It results in deafness from birth followed by loss of vision later in life; consequently, those with Usher'south syndrome often grow up in the Deaf customs using ASL, and later transition to TASL.[36] TASL differs from ASL in that signs are produced by touching the palms, and there are some grammatical differences from standard ASL in order to compensate for the lack of nonmanual signing.[25]

ASL changes over time and from generation to generation. The sign for telephone has changed equally the shape of phones and the manner of property them have changed.[37] The development of telephones with screens has also changed ASL, encouraging the utilise of signs that can be seen on minor screens.[37]

Stigma [edit]

In 2013, the White Business firm published a response to a petition that gained over 37,000 signatures to officially recognize American Sign Language as a community language and a language of teaching in schools. The response is titled "there shouldn't be any stigma about American Sign Language" and addressed that ASL is a vital language for the Deafened and difficult of hearing. Stigmas associated with sign languages and the use of sign for educating children often lead to the absence of sign during periods in children'south lives when they can access languages about finer.[38] Scholars such as Beth Due south. Benedict abet not only for bilingualism (using ASL and English training) but also for early on childhood intervention for children who are deafened. York University psychologist Ellen Bialystok has also campaigned for bilingualism, arguing that those who are bilingual larn cerebral skills that may help to foreclose dementia later in life.[39]

Well-nigh children born to deafened parents are hearing.[40] : 192 Known as CODAs ("Children Of Deaf Adults"), they are ofttimes more culturally Deaf than deaf children, about of whom are born to hearing parents.[40] : 192 Unlike many deafened children, CODAs acquire ASL as well as Deaf cultural values and behaviors from nascence.[40] : 192 Such bilingual hearing children may be mistakenly labeled equally beingness "slow learners" or as having "language difficulties" because of preferential attitudes towards spoken linguistic communication.[40] : 195

Writing systems [edit]

![]()

Although there is no well-established writing system for ASL,[41] written sign language dates back almost two centuries. The outset systematic writing system for a sign language seems to be that of Roch-Ambroise Auguste Bébian, adult in 1825.[42] : 153 However, written sign language remained marginal among the public.[42] : 154 In the 1960s, linguist William Stokoe created Stokoe notation specifically for ASL. Information technology is alphabetic, with a letter or diacritic for every phonemic (distinctive) hand shape, orientation, motion, and position, though it lacks any representation of facial expression, and is better suited for individual words than for extended passages of text.[43] Stokoe used that system for his 1965 A Lexicon of American Sign Language on Linguistic Principles.[44]

SignWriting, proposed in 1974 by Valerie Sutton,[42] : 154 is the starting time writing system to proceeds apply amongst the public and the first writing system for sign languages to be included in the Unicode Standard.[45] SignWriting consists of more than than 5000 distinct iconic graphs/glyphs.[42] : 154 Currently, it is in employ in many schools for the Deaf, specially in Brazil, and has been used in International Sign forums with speakers and researchers in more than 40 countries, including Brazil, Federal democratic republic of ethiopia, French republic, Frg, Italy, Portugal, Kingdom of saudi arabia, Slovenia, Tunisia, and the The states. Sutton SignWriting has both a printed and an electronically produced form so that persons tin can use the arrangement anywhere that oral languages are written (personal letters, newspapers, and media, academic research). The systematic examination of the International Sign Writing Alphabet (ISWA) as an equivalent usage structure to the International Phonetic Alphabet for spoken languages has been proposed.[46] According to some researchers, SignWriting is non a phonemic orthography and does not accept a one-to-one map from phonological forms to written forms.[42] : 163 That assertion has been disputed, and the procedure for each country to look at the ISWA and create a phonemic/morphemic assignment of features of each sign linguistic communication was proposed by researchers Msc. Roberto Cesar Reis da Costa and Madson Barreto in a thesis forum on June 23, 2014.[47] The SignWriting community has an open up projection on Wikimedia Labs to support the various Wikimedia projects on Wikimedia Incubator[48] and elsewhere involving SignWriting. The ASL Wikipedia asking was marked as eligible in 2008[49] and the test ASL Wikipedia has 50 articles written in ASL using SignWriting.

The most widely used transcription system amongst academics is HamNoSys, developed at the Academy of Hamburg.[42] : 155 Based on Stokoe Annotation, HamNoSys was expanded to about 200 graphs in order to permit transcription of any sign language.[42] : 155 Phonological features are usually indicated with single symbols, though the group of features that brand upward a handshape is indicated collectively with a symbol.[42] : 155

Comparison of ASL writing systems. Sutton SignWriting is on the left, followed by Si5s, then Stokoe annotation in the center, with SignFont and its simplified derivation ASL-phabet on the right.

Several boosted candidates for written ASL accept appeared over the years, including SignFont, ASL-phabet, and Si5s.

For English-speaking audiences, ASL is ofttimes glossed using English language words. Such glosses are typically all-capitalized and are arranged in ASL club. For instance, the ASL sentence DOG At present CHASE>Nine=3 CAT, meaning "the dog is chasing the true cat", uses Now to mark ASL progressive aspect and shows ASL verbal inflection for the third person (written with >Nine=3). However, glossing is not used to write the linguistic communication for speakers of ASL.[41]

Phonology [edit]

Phonemic handshape /ii/

[+ closed thumb][6] : 12

Phonemic handshape /3/

[− closed thumb][6] : 12

Each sign in ASL is composed of a number of distinctive components, more often than not referred to as parameters. A sign may use one hand or both. All signs tin can be described using the five parameters involved in signed languages, which are handshape, motion, palm orientation, location and nonmanual markers.[6] : 10 But as phonemes of sound distinguish significant in spoken languages, those parameters are the phonemes that distinguish meaning in signed languages like ASL.[50] Changing whatsoever i of them may modify the meaning of a sign, as illustrated by the ASL signs Call up and DISAPPOINTED:

|

|

There are too meaningful nonmanual signals in ASL,[6] : 49 which may include movement of the eyebrows, the cheeks, the nose, the head, the torso, and the eyes.[6] : 49

William Stokoe proposed that such components are analogous to the phonemes of spoken languages.[42] : 601:fifteen [e] There has also been a proposal that they are analogous to classes like place and manner of articulation.[42] : 601:15 Every bit in spoken languages, those phonological units tin can be separate into distinctive features.[half-dozen] : 12 For case, the handshapes /2/ and /3/ are distinguished by the presence or absence of the feature [± closed pollex], as illustrated to the correct.[6] : 12 ASL has processes of allophony and phonotactic restrictions.[half dozen] : 12, 19 There is ongoing research into whether ASL has an analog of syllables in spoken language.[vi] : 1

Grammar [edit]

Ii men and a woman signing

Morphology [edit]

ASL has a rich organisation of verbal inflection, which involves both grammatical aspect: how the action of verbs flows in fourth dimension—and agreement marking.[6] : 27–28 Aspect tin can be marked by changing the way of motility of the verb; for instance, continuous aspect is marked by incorporating rhythmic, circular movement, while punctual aspect is accomplished by modifying the sign so that it has a stationary manus position.[6] : 27–28 Verbs may agree with both the subject field and the object, and are marked for number and reciprocity.[half-dozen] : 28 Reciprocity is indicated by using two one-handed signs; for instance, the sign SHOOT, made with an Fifty-shaped handshape with inward movement of the thumb, inflects to SHOOT[reciprocal], articulated by having two L-shaped hands "shooting" at each other.[half-dozen] : 29

ASL has a productive arrangement of classifiers, which are used to classify objects and their motion in space.[six] : 26 For instance, a rabbit running downhill would employ a classifier consisting of a bent 5 classifier handshape with a downhill-directed path; if the rabbit is hopping, the path is executed with a bouncy mode.[6] : 26 In general, classifiers are composed of a "classifier handshape" bound to a "movement root".[6] : 26 The classifier handshape represents the object as a whole, incorporating such attributes every bit surface, depth, and shape, and is usually very iconic.[51] The movement root consists of a path, a direction and a fashion.[half-dozen] : 26

Fingerspelling [edit]

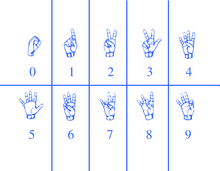

The American manual alphabet and numbers

ASL possesses a set of 26 signs known as the American manual alphabet, which tin be used to spell out words from the English language.[52] Such signs make utilize of the 19 handshapes of ASL. For example, the signs for 'p' and 'k' use the same handshape but different orientations. A common misconception is that ASL consists but of fingerspelling; although such a method (Rochester Method) has been used, information technology is not ASL.[35]

Fingerspelling is a class of borrowing, a linguistic process wherein words from ane language are incorporated into another.[35] In ASL, fingerspelling is used for proper nouns and for technical terms with no native ASL equivalent.[35] At that place are as well some other loan words which are fingerspelled, either very short English words or abbreviations of longer English words, eastward.thou. O-Due north from English 'on', and A-P-T from English 'flat'.[35] Fingerspelling may also exist used to emphasize a word that would commonly be signed otherwise.[35]

Syntax [edit]

ASL is a subject area–verb–object (SVO) linguistic communication, only diverse phenomena impact that basic discussion society.[53] Basic SVO sentences are signed without any pauses:[28]

FATHER

Dearest

Child

Begetter LOVE CHILD

"The father loves the kid."[28]

However, other word orders may also occur since ASL allows the topic of a sentence to exist moved to judgement-initial position, a miracle known as topicalization.[54] In object–subject–verb (OSV) sentences, the object is topicalized, marked past a frontwards head-tilt and a pause:[55]

Childtopic,

FATHER

Dear

CHILDtopic, Father Beloved

"The father loves the child."[55]

Likewise, word orders tin exist obtained through the miracle of subject re-create in which the subject is repeated at the end of the sentence, accompanied past head nodding for clarification or emphasis:[28]

Male parent

Dearest

Child

FATHERcopy

Father Love CHILD FATHERcopy

"The father loves the child."[28]

ASL also allows null subject area sentences whose subject is implied, rather than stated explicitly. Subjects can be copied even in a zilch subject sentence, and the discipline is then omitted from its original position, yielding a verb–object–subject (VOS) construction:[55]

LOVE

Kid

FATHERcopy

Beloved CHILD Fathercopy

"The father loves the child."[55]

Topicalization, accompanied with a null subject and a subject copy, tin can produce still some other discussion gild, object–verb–subject field (OVS).

CHILDtopic,

Love

FATHERcopy

CHILDtopic, LOVE Begettercopy

"The father loves the kid."[55]

Those properties of ASL allow information technology a multifariousness of discussion orders, leading many to question which is the true, underlying, "basic" society. At that place are several other proposals that attempt to business relationship for the flexibility of word guild in ASL. One proposal is that languages like ASL are all-time described with a topic–annotate structure whose words are ordered by their importance in the sentence, rather than by their syntactic backdrop.[56] Another hypothesis is that ASL exhibits free word order, in which syntax is non encoded in discussion club just can be encoded by other ways such as head nods, eyebrow movement, and body position.[53]

Iconicity [edit]

Mutual misconceptions are that signs are iconically self-explanatory, that they are a transparent fake of what they mean, or fifty-fifty that they are pantomime.[57] In fact, many signs acquit no resemblance to their referent because they were originally arbitrary symbols, or their iconicity has been obscured over time.[57] Withal, in ASL iconicity plays a significant role; a high percent of signs resemble their referents in some way.[58] That may be because the medium of sign, three-dimensional space, naturally allows more iconicity than oral linguistic communication.[57]

In the era of the influential linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, it was assumed that the mapping between form and meaning in linguistic communication must be completely arbitrary.[58] Although onomatopoeia is a clear exception, since words like 'choo-choo' comport clear resemblance to the sounds that they mimic, the Saussurean approach was to treat them every bit marginal exceptions.[59] ASL, with its significant inventory of iconic signs, straight challenges that theory.[sixty]

Research on acquisition of pronouns in ASL has shown that children do not ever take advantage of the iconic properties of signs when they interpret their pregnant.[61] It has been constitute that when children acquire the pronoun "you", the iconicity of the point (at the child) is ofttimes confused, beingness treated more than like a name.[62] That is a similar finding to research in oral languages on pronoun conquering. It has also been found that iconicity of signs does not affect immediate memory and retrieve; less iconic signs are remembered just too every bit highly-iconic signs.[63]

See besides [edit]

- American Sign Language grammar

- American Sign Language literature

- Babe sign language

- Bimodal bilingualism

- Nifty ape language, of which ASL has been one attempted mode

- Legal recognition of sign languages

- Pointing

- Sign proper noun

- ASL interpreting

Notes [edit]

- ^ In particular, Martha's Vineyard Sign Linguistic communication, Henniker Sign Language, and Sandy River Valley Sign Language were brought to the school by students. They, in turn, appear to have been influenced by early British Sign Language and did not involve input from indigenous Native American sign systems. Come across Padden (2010:11), Lane, Pillard & French (2000:17), and Johnson & Schembri (2007:68).

- ^ The Abbé Charles-Michel de l'Épée, founder of the Parisian school Institut National de Jeunes Sourds de Paris, was the beginning to acknowledge that sign language could be used to educate the deaf. An oft-repeated folk tale states that while visiting a parishioner, Épee met two deaf daughters conversing with each other using LSF. The mother explained that her daughters were being educated privately past means of pictures. Épée is said to have been inspired by those deaf children when he established the first educational institution for the deafened.[18]

- ^ Whereas deafness was genetically recessive on Martha's Vineyard, information technology was ascendant in Henniker. On the one hand, this dominance likely aided the development of sign linguistic communication in Henniker since families would be more likely to take the critical mass of deafened people necessary for the propagation of signing. On the other hand, in Martha's Vineyard the deaf were more likely to have more than hearing relatives, which may take fostered a sense of shared identity that led to more than inter-group communication than in Henniker.[19]

- ^ Although some surveys of smaller scope measure ASL use, such as the California Section of Instruction recording ASL use in the home when children begin school, ASL use in the general American population has not been straight measured. Encounter Mitchell et al. (2006:1).

- ^ Stokoe himself termed them cheremes, but other linguists accept referred to them as phonemes. Meet Bahan (1996:11).

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d e f k h i j k l Mitchell et al. (2006)

- ^ Province of Ontario (2007). "Bill 213: An Human action to recognize sign language equally an official language in Ontario". Archived from the original on 2018-12-24. Retrieved 2015-07-23 .

- ^ Pedagogy Policy Counsel at National Clan of the Deaf. "States that Recognize American Sign Language every bit a Foreign Linguistic communication" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved xiii February 2022.

- ^ About American Sign Language, Deafened Research Library, Karen Nakamura

- ^ "American Sign Linguistic communication". NIDCD. 2015-08-eighteen. Retrieved 2021-03-08 .

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m due north o p q r s t u 5 w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag Bahan (1996)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j thou l m north Padden (2010)

- ^ a b c d e Kegl (2008)

- ^ a b c d Johnson & Schembri (2007)

- ^ "ASL as a Foreign Language Fact Sail". www.unm.edu . Retrieved 2015-11-04 .

- ^ Wilcox Phd, Sherman (May 2016). "Universities That Accept ASL In Fulfillment Of Foreign Linguistic communication Requirements". Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- ^ Burke, Sheila (April 26, 2017). "Bill Passes Requiring Sign Language Students Receive Credit". U.s.a. News. Archived from the original on 2017-ten-xi. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- ^ Ceil Lucas, 1995, The Sociolinguistics of the Deaf Community

- ^ Lane, Pillard & French (2000:17)

- ^ Groce, Nora Ellen (1985). Everyone Here Spoke Sign Language: Hereditary Deafness on Martha'south Vineyard . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Printing. ISBN978-0-674-27041-one . Retrieved 21 October 2010.

anybody hither sign.

- ^ a b c d "A Brief History of ASD". American School for the Deaf. due north.d. Archived from the original on March 1, 2014. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

- ^ "A Cursory History Of The American Asylum, At Hartford, For The Education And Instruction Of The Deaf And Dumb". 1893. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

- ^ See:

- Ruben, Robert J. (2005). "Sign language: Its history and contribution to the agreement of the biological nature of language". Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 125 (5): 464–vii. doi:x.1080/00016480510026287. PMID 16092534. S2CID 1704351.

- Padden, Carol A. (2001). Folk Explanation in Language Survival in: Deaf World: A Historical Reader and Chief Sourcebook, Lois Bragg, Ed. New York: New York University Press. pp. 107–108. ISBN978-0-8147-9853-ix.

- ^ See Lane, Pillard & French (2000:39).

- ^ a b c d e f Armstrong & Karchmer (2002)

- ^ Stokoe, William C. 1960. Sign Linguistic communication Structure: An Outline of the Visual Communication Systems of the American Deaf, Studies in linguistics: Occasional papers (No. viii). Buffalo: Dept. of Anthropology and Linguistics, University of Buffalo.

- ^ "American Sign Language, ASL or Ameslan". Handspeak.com. Archived from the original on 2013-06-05. Retrieved 2012-05-21 .

- ^ a b c d due east Nyst (2010)

- ^ Benoit Duchateau-Arminjon, 2013, Healing Cambodia One Child at a Time, p. 180.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j m l American Sign Language at Ethnologue

- ^ Rogelio, Contreras (November fifteen, 2002). "Regional, Cultural, and Sociolinguistic Variation of ASL in the United States".

- ^ Gallaudet Section of Linguistics (2017-09-16), Do sign languages have accents?, archived from the original on 2021-10-30, retrieved 2018-04-27

- ^ a b c d e f Valli, Clayton (2005). Linguistics of American Sign Language: An Introduction. Washington, D.C.: Clerc Books. p. 169. ISBN978-1-56368-283-4.

- ^ a b c d Bailey & Dolby (2002:one–two)

- ^ Lucas, Bayley & Valli (2003:36)

- ^ a b c d e Solomon (2010)

- ^ Bolivian Sign Language at Ethnologue

- ^ Hurlbut (2003, seven. Decision)

- ^ a b c Nakamura, Karen (2008). "Nigh ASL". Deafened Resource Library. Retrieved December 3, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Costello (2008:xxv)

- ^ Collins (2004:33)

- ^ a b Morris, Amanda (2022-07-26). "How Sign Language Evolves as Our World Does". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-07-28 .

- ^ Newman, Aaron J.; Bavelier, Daphne; Corina, David; Jezzard, Peter; Neville, Helen J. (2002). "A critical period for right hemisphere recruitment in American Sign Linguistic communication processing". Nature Neuroscience. v (1): 76–80. doi:10.1038/nn775. PMID 11753419. S2CID 2745545.

- ^ Denworth, Ldyia (2014). I Can Hear Y'all Whisper: An Intimate Journey through the Science of Sound and Language. USA: Penguin Group. p. 293. ISBN978-0-525-95379-ane.

- ^ a b c d Bishop & Hicks (2005)

- ^ a b Supalla & Cripps (2011, ASL Gloss as an Intermediary Writing System)

- ^ a b c d eastward f g h i j van der Hulst & Channon (2010)

- ^ Armstrong, David F., and Michael A. Karchmer. "William C. Stokoe and the Study of Signed Languages." Sign Language Studies 9.4 (2009): 389-397. Academic Search Premier. Spider web. 7 June 2012.

- ^ Stokoe, William C.; Dorothy C. Casterline; Carl One thousand. Croneberg. 1965. A dictionary of American sign languages on linguistic principles. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet College Press

- ^ Everson, Michael; Slevinski, Stephen; Sutton, Valerie. "Proposal for encoding Sutton SignWriting in the UCS" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ^ Charles Butler, Center for Sutton Move Writing, 2014

- ^ Roberto Costa; Madson Barreto. "SignWriting Symposium Presentation 32". signwriting.org.

- ^ "Exam wikis of sign languages". incubator.wikimedia.org.

- ^ "Request for ASL Wikipedia". meta.wikimedia.org.

- ^ Baker, Anne; van den Bogaerde, Beppie; Pfau, Roland; Schermer, Trude (2016). The Linguistics of Sign Languages : An Introduction. John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN9789027212306.

- ^ Valli & Lucas (2000:86)

- ^ Costello (2008:xxiv)

- ^ a b Neidle, Carol (2000). The Syntax of American Sign Language: Functional Categories and Hierarchical Structures. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. p. 59. ISBN978-0-262-14067-6.

- ^ Valli, Clayton (2005). Linguistics of American Sign Language: An Introduction. Washington, D.C.: Clerc Books. p. 85. ISBN978-1-56368-283-four.

- ^ a b c d e Valli, Clayton (2005). Linguistics of American Sign Linguistic communication: An Introduction. Washington, D.C.: Clerc Books. p. 86. ISBN978-i-56368-283-4.

- ^ Lillo-Martin, Diane (November 1986). "Two Kinds of Null Arguments in American Sign Language". Natural Language and Linguistic Theory. iv (4): 415. doi:10.1007/bf00134469. S2CID 170784826.

- ^ a b c Costello (2008:xxiii)

- ^ a b Liddell (2002:threescore)

- ^ Liddell (2002:61)

- ^ Liddell (2002:62)

- ^ Thompson, Robin L.; Vinson, David P.; Vigliocco, Gabriella (March 2009). "The Link Betwixt Form and Pregnant in American Sign Linguistic communication: Lexical Processing Effects". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 35 (2): 550–557. doi:ten.1037/a0014547. ISSN 0278-7393. PMC3667647. PMID 19271866.

- ^ Petitto, Laura A. (1987). "On the autonomy of language and gesture: Show from the acquisition of personal pronouns in American sign language". Cognition. 27 (1): 1–52. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(87)90034-v. PMID 3691016. S2CID 31570908.

- ^ Klima & Bellugi (1979:27)

Bibliography [edit]

- Armstrong, David; Karchmer, Michael (2002), "William C. Stokoe and the Study of Signed Languages", in Armstrong, David; Karchmer, Michael; Van Cleve, John (eds.), The Study of Signed Languages, Gallaudet University, pp. 11–xix, ISBN978-ane-56368-123-3 , retrieved November 25, 2012

- Bahan, Benjamin (1996). Non-Transmission Realization of Agreement in American Sign Language (PDF). Boston University. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 11, 2017. Retrieved Nov 25, 2012.

- Bailey, Carol; Dolby, Kathy (2002). The Canadian dictionary of ASL. Edmonton, AB: The University of Alberta Press. ISBN978-0888643001.

- Bishop, Michele; Hicks, Sherry (2005). "Orange Eyes: Bimodal Bilingualism in Hearing Adults from Deaf Families". Sign Language Studies. v (2): 188–230. doi:x.1353/sls.2005.0001. S2CID 143557815.

- Collins, Steven (2004). Adverbial Morphemes in Tactile American Sign Language. Union Institute & University.

- Costello, Elaine (2008). American Sign Language Lexicon . Random House. ISBN978-0375426162 . Retrieved Nov 26, 2012.

- Hurlbut, Hope (2003), "A Preliminary Survey of the Signed Languages of Malaysia", in Baker, Anne; van den Bogaerde, Beppie; Crasborn, Onno (eds.), Cross-linguistic perspectives in sign language research: selected papers from TISLR (PDF), Hamburg: Signum Verlag, pp. 31–46, archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09, retrieved December iii, 2012

- Johnson, Trevor; Schembri, Adam (2007). Australian Sign Language (Auslan): An introduction to sign language linguistics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0521540568 . Retrieved November 27, 2012.

- Kegl, Judy (2008). "The Example of Signed Languages in the Context of Pidgin and Creole Studies". In Kouwenberg, Silvia; Singler, John (eds.). The Handbook of Pidgin and Creole Studies. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN978-0521540568 . Retrieved November 27, 2012.

- Klima, Edward S.; Bellugi, Ursula (1979). The signs of language . Boston: Harvard University Press. ISBN978-0-674-80796-9.

- Lane, Harlan; Pillard, Richard; French, Mary (2000). "Origins of the American Deaf-World". Sign Linguistic communication Studies. one (1): 17–44. doi:10.1353/sls.2000.0003.

- Liddell, Scott (2002), "Modality Furnishings and Conflicting Agendas", in Armstrong, David; Karchmer, Michael; Van Cleve, John (eds.), The Study of Signed Languages, Gallaudet University, pp. xi–xix, ISBN978-1-56368-123-3 , retrieved Nov 26, 2012

- Lucas, Ceil; Bayley, Robert; Valli, Clayton (2003). What's your sign for pizza?: An introduction to variation in American Sign Language. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Printing. ISBN978-1563681448.

- Mitchell, Ross; Young, Travas; Bachleda, Bellamie; Karchmer, Michael (2006). "How Many People Use ASL in the United states of america?: Why Estimates Need Updating" (PDF). Sign Linguistic communication Studies. 6 (iii). ISSN 0302-1475. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved November 27, 2012.

- Nyst, Victoria (2010), "Sign languages in West Africa", in Brentari, Diane (ed.), Sign Languages, Cambridge University Press, pp. 405–432, ISBN978-0-521-88370-2

- Padden, Carol (2010), "Sign Language Geography", in Mathur, Gaurav; Napoli, Donna (eds.), Deaf Around the Globe (PDF), New York: Oxford University Press, pp. xix–37, ISBN978-0199732531, archived from the original (PDF) on June 3, 2011, retrieved November 25, 2012

- Solomon, Andrea (2010). Cultural and Sociolinguistic Features of the Blackness Deaf Community (Honors Thesis). Carnegie Mellon University. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- Supalla, Samuel; Cripps, Jody (2011). "Toward Universal Design in Reading Instruction" (PDF). Bilingual Basics. 12 (2). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved January 5, 2012.

- Valli, Clayton; Lucas, Ceil (2000). Linguistics of American Sign Language. Gallaudet University Printing. ISBN978-1-56368-097-vii . Retrieved December ii, 2012.

- van der Hulst, Harry; Channon, Rachel (2010), "Notation systems", in Brentari, Diane (ed.), Sign Languages, Cambridge University Press, pp. 151–172, ISBN978-0-521-88370-2

External links [edit]

![]()

- American Sign Language at Curlie

- Accessible American Sign Language vocabulary site

- American Sign Language give-and-take forum

- One-stop resource American Sign Linguistic communication and video lexicon

- National Institute of Deafness ASL department

- National Clan of the Deafened ASL information

- American Sign Language

- The American Sign Language Linguistics Research Project

- Video Dictionary of ASL

- American Sign Language Dictionary

Asl Sign For What Happened,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Sign_Language

Posted by: taylorwhick1956.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Asl Sign For What Happened"

Post a Comment